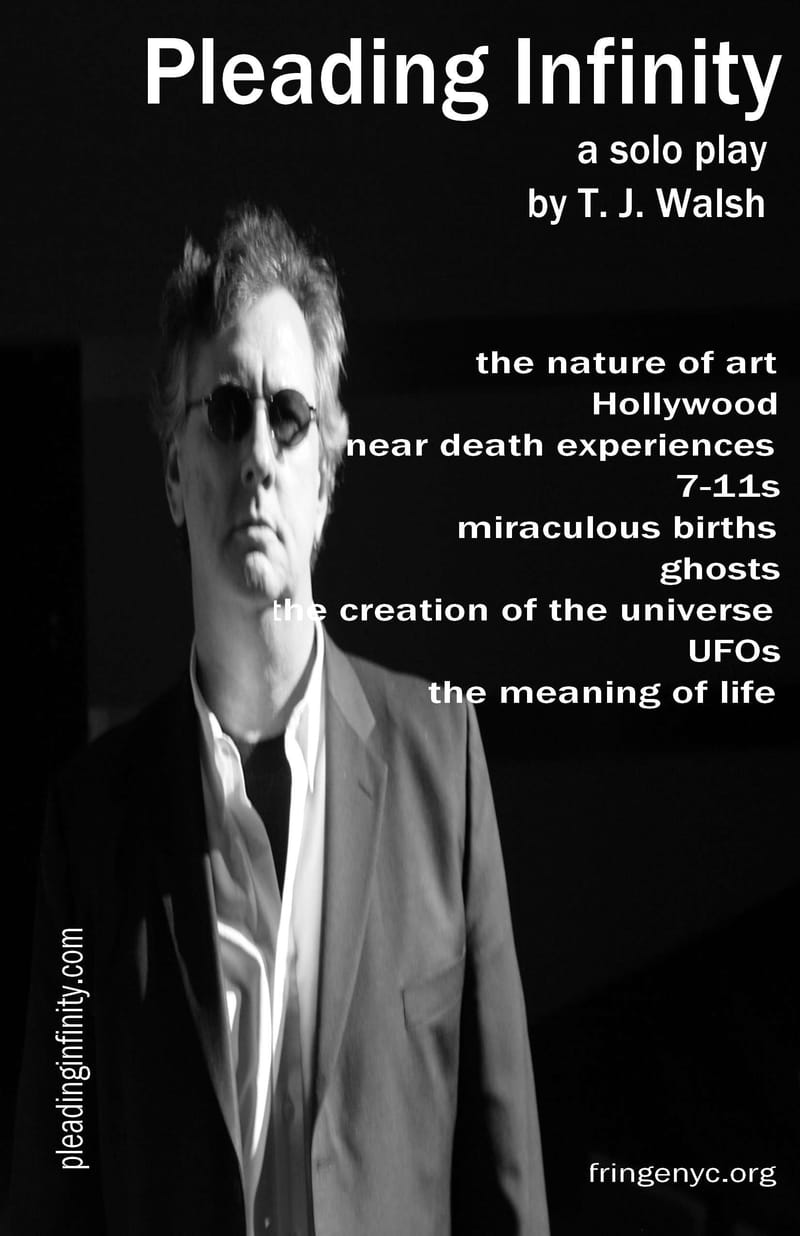

Pleading Infinity

nytheatre.com review

reviewed by Todd Carlstrom · NY International Fringe Festival

"I'm going to be frank: seeing a one-person show makes me worried. It's more of an all-or-nothing proposition than a multi-character offering, simply because I'm charging one single person with my evening's entertainment. Fortunately, in the six monologues that comprise Pleading Infinity, T.J. Walsh proves himself eminently worthy of such responsibility, both as writer and performer.

The main character is a successful screenwriter named Bob Donovan whose cliquish Hollywood name-dropping initially gives the impression of shallowness. He knows how to spin a yarn, however, and as the first three monologues are about an alien abduction, a near-death experience, and a haunted house, respectively, he's got great material to work with. Walsh's brash humor and easygoing manner make him a captivating storyteller, even if he rarely moves from his chair.

Infinity is billed as "a solo play," a distinction that might not seem to matter much at first blush, especially as there are no overtly expressed connections between the early monologues. Indeed, I began to wonder if the play was just a novelty piece about a guy who's had a lot of traffic in the extraordinary. As the show progresses, however, the emotional arc of Bob's journey moves to the fore. This is Walsh's real accomplishment, both as playwright and actor, and is all the more remarkable for the subtlety with which it occurs.

His abduction story seems almost a lark, and its punchline ending seems to confirm that Donovan isn't the introspective type, and may even be a liar. However, after his brush with death, during which he leaves his body and meets with his dead mother, Bob begins to seek answers to the big questions raised by his encounters with the supernatural. "Do you believe in God?" he asks repeatedly in the second monologue. At first that seems like a lark, too, like he's just using it to challenge the audience, but it is a theme that resurfaces over and over. As he reveals details about his family life, both as a child and now as a husband and father, his priorities come into focus, and an unexpected tenderness emerges gracefully from the script. His gradual transformation from thoughtless cynicism to spiritual self-realization happens (super)naturally, never seeming forced.

The tone veers dangerously close to melodrama in the fourth monologue, in which he finds himself birthing a homeless woman's baby in a convenience store, but Walsh's ability to keep your attention on the bigger picture makes the sentimentality forgivable. The fifth installment recounts a Hollywood studio head's careless dismantling of the screenplay Bob wrote about his experiences, and the huge life decision it brings Bob to. He is at his most poignant in the final monologue, in which he connects with his estranged father, who abandoned the family when Bob's mother was dying in a hospice.

Perhaps the most amazing aspect of this production is that no director or designers are credited, presumably meaning that Walsh did it all himself. It takes enough talent to write and perform a script of such nuance, but to have brought it to the stage without the help of another, more objective set of eyes with that nuance intact is a tremendous achievement."

a solo play by T.J. Walsh

Pleading Infinity

a solo play by T.J. Walsh

In this funny and moving solo play Bob Donovan, Hollywood screenwriter, wrestles with life’s big questions including miraculous births, the nature of art, near death experiences, ghosts, UFOs, the creation of the universe, and, finally, the meaning of life.

“A polished and mature piece…very funny and touching monologues chronicling the life of screenwriter Bob Donovan.” Austin American Statesman

Pleading Infinity was developed in Austin, Texas at FronteraFest, the premier fringe festival of the Southwest and performed at the New York International Fringe Festival, the Hollywood Fringe Festival and the reading series at Fort Worth's Amphibian Productions and the Dallas/Fort Worth Dramatist Guild Reading Series.

“As the play progresses the emotional arc of Bob’s journey moves to the fore. This is Walsh’s real accomplishment, and is all the more remarkable for the subtlety with which it occurs.” NYTheatre.com

AWARDS

Our Chicago production of Pleading Infinity starring Jon Barnes as Bob Donovan was nominated for five BroadwayWorld-Chicago awards.

Voting has begun for the "Broadway World - Chicago" Awards "Pleading Infinity" is nominated in five (5) categories 1. Best Play - "Pleading Infinity"

2. Best New Play or Musical - "Pleading Infinity"

3. Best Performer in a Play - Jon Barnes "Pleading Infinity"

4. Best Director - T.J. Walsh "Pleading Infinity"

5. Best Cabaret/Concert/Solo Performance - Jon Barnes "Pleading Infinity"

Voting has begun for the "Broadway World - Chicago" Awards "Pleading Infinity" is nominated in five (5) categories 1. Best Play - "Pleading Infinity"

2. Best New Play or Musical - "Pleading Infinity"

3. Best Performer in a Play - Jon Barnes "Pleading Infinity"

4. Best Director - T.J. Walsh "Pleading Infinity"

5. Best Cabaret/Concert/Solo Performance - Jon Barnes "Pleading Infinity"

CHICAGO June 29-August 3, 2023

The Annoyance Theatre and Bar, 851 W. Belmont Avenue

Curtain is at 6:30pm.

It plays every Thursday night through August 3.

Tickets: $15

For tickets and information call 773-697-6963

Online tickets at

https://theannoyance.thundertix.com/events/213730/performances

Ticket Discount: 25% discount with code PLIN25

ONLINE REVIEW:

"I attended the June 29 performance of "Pleading Infinity". I am not normally a fan of "one-person shows" - but this production of "Pleading Infinity" is VERY, VERY IMPRESSIVE! I enjoyed the way the script is structured ... and the dialogue is well-written. Combine that conversational dialogue with the exceptional performance of Jon Barnes - - - and this is a wonderful, FIRST-RATE PRODUCTION definitely worthy of Joseph Jefferson Award consideration. Mr. Barnes' performance was truly so believable, I never thought he was reading a script. I thought he was telling "HIS STORY" to us. There shouldn't be an empty chair in the Small Theatre."

Curtain is at 6:30pm.

It plays every Thursday night through August 3.

Tickets: $15

For tickets and information call 773-697-6963

Online tickets at

https://theannoyance.thundertix.com/events/213730/performances

Ticket Discount: 25% discount with code PLIN25

ONLINE REVIEW:

"I attended the June 29 performance of "Pleading Infinity". I am not normally a fan of "one-person shows" - but this production of "Pleading Infinity" is VERY, VERY IMPRESSIVE! I enjoyed the way the script is structured ... and the dialogue is well-written. Combine that conversational dialogue with the exceptional performance of Jon Barnes - - - and this is a wonderful, FIRST-RATE PRODUCTION definitely worthy of Joseph Jefferson Award consideration. Mr. Barnes' performance was truly so believable, I never thought he was reading a script. I thought he was telling "HIS STORY" to us. There shouldn't be an empty chair in the Small Theatre."

Audience Reactions

Audience Reactions

FORT WORTH FRINGE FESTIVAL

September 8, 9, 10, 2023

September 8, 9, 10, 2023

The Gallery Theatre - fwfringe.com

an intimate theater in the Fort Worth Arts Center

1300 Gendy Street, Fort Worth, TX 76107

Friday, September 8: 6:20pm Curtain

Saturday, September 9: 2:10pm Curtain

Saturday, September 9: 4:50pm Curtain

Sunday, September 10: 7:00pm Curtain

For Tickets:

https://buy.ticketstothecity.com/purchase.php?event_id=12922

Pleading Infinity will run 60 minutes without an intermission.

an intimate theater in the Fort Worth Arts Center

1300 Gendy Street, Fort Worth, TX 76107

Friday, September 8: 6:20pm Curtain

Saturday, September 9: 2:10pm Curtain

Saturday, September 9: 4:50pm Curtain

Sunday, September 10: 7:00pm Curtain

For Tickets:

https://buy.ticketstothecity.com/purchase.php?event_id=12922

Pleading Infinity will run 60 minutes without an intermission.

PLEADING INFINITY at

the Dramatists Guild Reading Series

the Dramatists Guild Reading Series

criticalrant.com Alexandra Bonifield

Theater Reviews & Perspectives: Reflect, Intersect, Inspire

"Regional playwright and author, professional stage director and TCU theatre professor T.J. Walsh brought his mysterious yet poignant PLEADING INFINITY to the Core Theatre, as part of The Dramatist Guild Reading Series. The quirky, engaging show featured veteran actor and Texas Wesleyan professor Richard Haratine. Negotiating plot twists reminiscent of The Twilight Zone, the solo actor plays a screenwriter revealing conversationally his life experiences relating to Hollywood, near death moments, birth, ghostly haunting, UFO visitation, the nature of art and the universe’s emergence."

"Beautifully crafted as a literary work and acted equally well, the show provides intrigue and charm as it glides towards completion as a work. Superior script by Walsh meets sterling performance by Haratine."

Pleading Infinity at the Hollywood Fringe Festival

ONLINE REVIEWS:

"Taught pacing, excellent story telling. I am certainly no stranger to live theater but I will never forget the hour and a half I spent with the character Bob Donovan. Truly unforgettable. So much so that I actually took the time to write an online review. Bravo."

"Brilliant. We thoroughly enjoyed the show. Beautiful, fun, funny, moving. The time flew by. Loved the actor. An interesting and fun ride through the adventures of Bob Donovan, successful Hollywood screen writer. We plan to see it again!"

"Jon Ebeling’s acting was superb and compelling – a wonderful balance of funny and heartwarming. I liked that the play was structured as 6 separate vignettes woven into 1 larger story. Engaging storytelling. I thoroughly enjoyed going on this journey."

"This show was a blast! Great writing. I laughed, cried, and left a happy man. The writing is brilliant, the set and music was perfect! Seriously, it does not seem like a 90 minute show. My friends and I were so surprised it was over. We had a great time."

"Taught pacing, excellent story telling. I am certainly no stranger to live theater but I will never forget the hour and a half I spent with the character Bob Donovan. Truly unforgettable. So much so that I actually took the time to write an online review. Bravo."

"Brilliant. We thoroughly enjoyed the show. Beautiful, fun, funny, moving. The time flew by. Loved the actor. An interesting and fun ride through the adventures of Bob Donovan, successful Hollywood screen writer. We plan to see it again!"

"Jon Ebeling’s acting was superb and compelling – a wonderful balance of funny and heartwarming. I liked that the play was structured as 6 separate vignettes woven into 1 larger story. Engaging storytelling. I thoroughly enjoyed going on this journey."

"This show was a blast! Great writing. I laughed, cried, and left a happy man. The writing is brilliant, the set and music was perfect! Seriously, it does not seem like a 90 minute show. My friends and I were so surprised it was over. We had a great time."